A bit more about this project!

Since September 2019, I have had the pleasure to be the writer in residence at the Arnolfini art gallery, here in Bristol, writing mainly on feminism, women artists and themes around resistance, worldwide. The exhibitions I covered include the feminist show ‘Still I Rise’, Amak Mahmoodian’s ‘Zanjir’, Angelica Mesiti’s ‘Assembly’ and later on, after the lockdown, Hassan Hajjaj’s ‘The Path’.

During the lockdown, the gallery had the idea of assembling a little art book, more than commissioning other blog posts, so they asked me if I’d like to work on a text dedicated to all the African, Caribbean and Afro-Caribbean British artists, the ones they invited to exhibit over the years since their opening in 1961.

It sounded so very relevant to me, as I’ve spent most of my adult life as a reporter on African news, on or in Africa, and worked lengthily for a film production company stemming from Haiti. I started working on a book that is now to me a sort of short history of what could be designated as “Black Art” in the UK and beyond.

As we’re now in the middle of Black History Month in the UK, I feel it’s a good time to say a bit more about them and this book.

Focus on black artists who made history

These include British artists like Veronica Ryan, Keith Piper and Donald Rodney – two key members of the ‘Black Art Group’ in the 1980s, but also a history of Carnival festivities, artists who took part in the Harlem Renaissance in New York in the 20thcentury, and some brilliant filmmakers and video artists like John Akomfrah. Some were born in the UK, others in Trinidad, Jamaica, Morocco, Sudan or Ghana…

This project gives me room to try to weave together the different parts of the African continent and the “triangular” routes that binds it to America and Europe. These themes have haunted my own work as a journalist, researcher and writer since the mid-2000s as well.

One example: My favourite show at the Arnolfini was definitely ‘Vertigo Sea’ by Ghanaian British filmmaker John Akomfrah. His work with the Black Audio Film Collective and lately Smoking Dogs Film definitely challenged this recent history of cinema and political art. Another relevant show I’ll cover in this book ‘Trophies of Empire’, and I had a very insightful discussions about it with artists and curators such as Keith Piper, Nav Haq and Graeme Evelyn, notably on what ‘Black Art’ really means, how this notion constantly evolves between a political meaning to a more sociological perspective or even, more recently, a strictly racial views.

In the 1970s, the most radical ‘Black’ British artists was probably Rasheed Araeen, who born in 1935 in Karachi and is therefore Pakistani, not African. In the 1980s, Jamaican and other Caribbean/South American British artists like Sonia Boyce and Frank Bowling revolutionised the artistic landscape. Since then, African British artists took centre stage like John Akomfrah and Lubaina Himid, whom I interviewed a few months before she received the Turner Prize. More recently artists from Nigeria, Morocco or Algeria have also left their mark, and been invited to key British art centre like The Arnolfini and the Hayward Gallery in Londone. It is a fascinating journey, everything but one-sided.

Bristol: A bridge between England, the Caribbean and Africa

Before I came to Bristol to start my research on the ‘Bristol Sound’ in 2015, I had lived in Paris, Prague and Miami, travelling to Haiti before settling in London. I then moved to Africa, living in Kenya, travelling to Uganda, Tanzania, Somalia, Central Africa and Liberia, which changed my view of the UK and the western world in general…

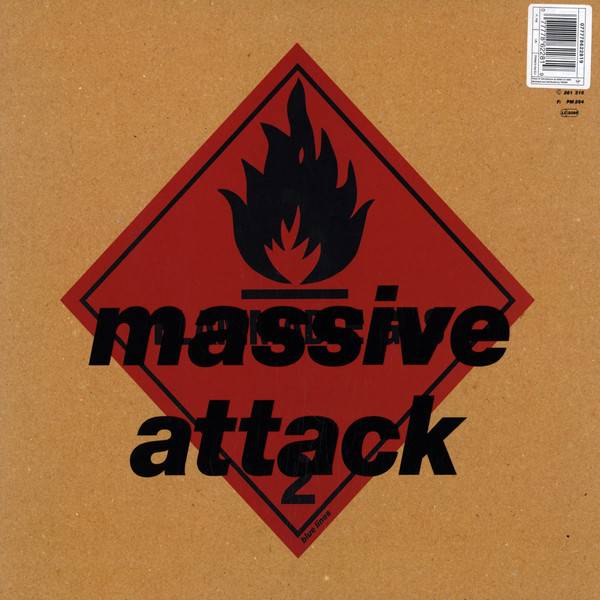

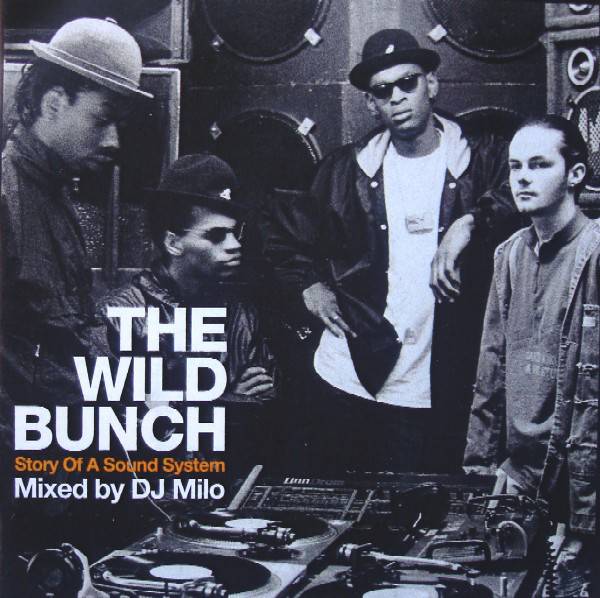

And in a way, after these experiences, Bristol too shifted my perception of the UK, because its history is so much more overtly linked to the triangular trade with the Americas and Africa, and therefore to displacements and slavery. I first came to Bristol to visit Massive Attack’s studio when the city was the European Green Capital. Quickly, Bristol became both an exciting territory to explore, and a familiar cosy second home. It’s quite a peculiar experience.

Since then, Brexit followed, making myself not a welcome guest but an immigrant potentially facing a loss of civic rights, or even departure. More recently, Edward Colston’s statue was torn down, a complete watershed moment for Black Bristolians, after years of campaigning from different organisations and artists. I had much earlier discussed Colston with Massive Attack, who had always demanded a change of name for the auditorium bearing his name.

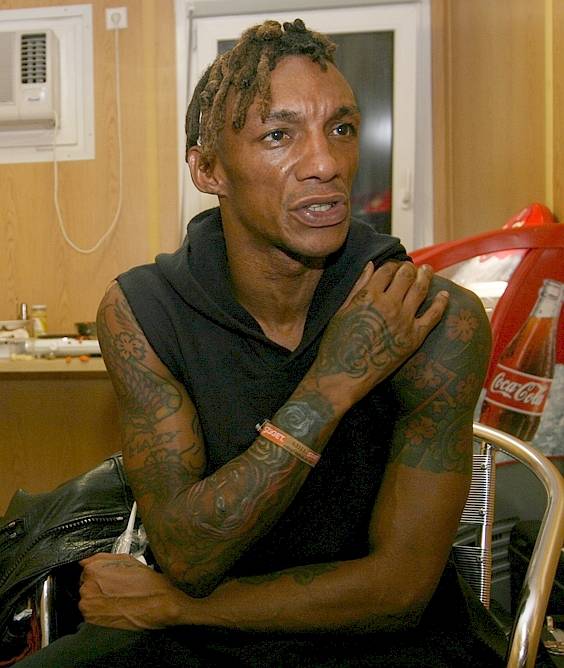

Over the years, writing about artists like Tricky, Mad Professor (the genius of dub music) or even Banksy embodied a story that included the consequences of colonialism, here in Britain, in the Caribbean, in Africa but also in Palestine or Iraq. These are the issues that have pervaded throughout everything I do as a journalist, writer, or researcher because they define our modern civilisation.

Moreover, my own family is from North Africa, which is a part of the continent that is underreported in the English-speaking world; North African people are almost never mentioned, let alone artists. The Arnolfini however did receive artists from Sudan, Algeria, Morocco and Egypt; so did the Watershed cinema with films. Elsewhere in Bristol, my experience is that Bristolians can be very vocal, quite territorial, and polarised on the relations between white English citizens and their Caribbean counterparts.

That leaves very little room to bring in voices from South Asia, South America, East Africa, the Middle East or North Africa – where other people of colour have a different but sometimes really relevant experience of colonialism, religions and racism. I even feel sometimes that it’s delusional to want to be part of such a city. This is compounded by Brexit and misrepresented debates on history, polarised divisions and also high inequalities.

So more than ever, writing about art opens a way to relate to a different community, beyond borders and beyond the ‘colour line’, around shared values of inclusivity, creativity and knowledge.

My book for the Arnolfini is still a work in progress. I’ve looked into catalogues and archives, reflected on the meaning of these artists’ works, on different levels. I’ve been in touch with some of the artists and curators involved: some have sent me some articles, links, video recordings about their art, from back then and now; others have had time for an interview.

My own memories of some of the exhibitions, or encounters with these artists’ work in other places, as well as some of my research done from 2015 for my previous book, on Bristol’s music scene, also nourished this project.

What I know for sure is that writing about such socially aware and even sometimes politically engaged art allows much more depth. It enables – just like my work in fiction – one to dig into different sorts of subjectivities, recognised and accepted as such, to explain our very complex world with multiple shades of colours.

Ed: Melissa’s book will be out in March 2021, as part of the celebrations for the 60 years of Arnolfini.

Arnolfini is Bristol’s International Centre for Contemporary Arts located on the harbourside in the heart of the city.

-

Link to West England Bylines: https://westenglandbylines.co.uk/african-art-at-the-arnolfini-bristol/

.jpg)