Reading back some comments about Franz Kafka for a new project, I'm reminded that one of his first trips outside of Prague was in Heligoland, the then British island, now off Germany in the Northern Sea.

Franz Kafka | |

| 1883 | Am 3. Juli 1883 wird Franz Kafka in Prag geboren. Er ist das älteste Kind des Kaufmanns Hermann Kafka. Zwei nach ihm geborene Brüder sterben schon im Säuglingsalter. Seine drei Schwestern werden später von den Nazis verschleppt. Ihre Spuren haben sich verloren. |

| 1889-1901 | Nach der "Deutschen Knabenschule" besucht Franz Kafka das humanistische Staatsgymnasium. Bereits als Schüler schreibt er, vernichtet jedoch die Frühwerke allesamt. |

| 1901 | Nach dem bestandenen Abitur macht Franz Kafka Ferien auf den Inseln Norderney und Helgoland. Im Herbst nimmt er ein Studium an der Universität zu Prag auf. Er belegt Chemie, anschließend Jura. Zusätzlich besucht er Vorlesungen in Kunstgeschichte. |

http://blog.wellcomelibrary.org/2013/03/the-red-white-and-green-of-germany/

The Red, White and Green of ….Germany?

04/03/2013

When we talk about our archives and manuscripts, our focus is usually on their content. People order archive items in order to read them, by and large, and our catalogues tend to focus upon the words on the page, and their meaning, rather the detailed nature of that page. Scholars of medieval manuscripts will also look at the physical makeup of a volume – it may, for instance, form only a part of a larger whole whose other parts are elsewhere, or have been assembled from disparate pieces years after these were written – and accordingly catalogue records for medieval manuscripts do go into more detail about this aspect of a manuscript. In general, however, catalogue records for post-medieval material are silent about the medium on which the words are written and focus purely on their meaning.

And yet, one of the abiding fascinations of archive material is its physicality: the sensation of touching the past, of contact across the centuries. Periodically something about an archive item will wake this interest in the physical object. It may be something as simple as the autograph of a famous person, such as Darwin or Dickens, or a doodle that catches the moment at which a thought takes shape. Sometimes, however, it is something about the sheet of paper itself, something unrelated to the content of the words: the thick black border that marks the point that someone goes into mourning, for instance, or the letterhead that sits, often ignored, above the writing.

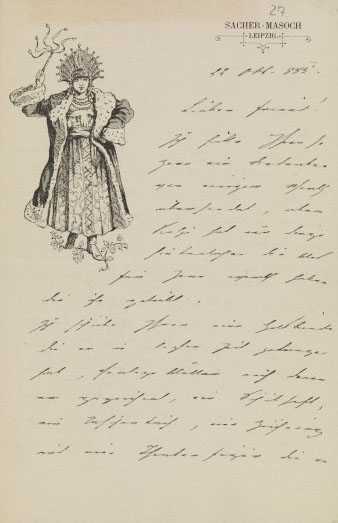

One such letterhead opens a window into a little-known corner of Europe, and its history. The Library holds a collection of 98 pieces of correspondence relating to the Austrian writer Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, whose novel “Venus in Furs”, recounting a sexual relationship based on punishment and humiliation doled out by a dominant woman, is the origin of the word “masochism”. (For more detail on our Sacher-Masoch holdings see the archives catalogue here or an earlier blog posting on a twentieth-century reimagining of his fiction.)

Sacher-Masoch’s personal letterhead is well worth a glance, showing a woman in furs brandishing a whip in a scene recalling his fiction. In 1890, however, he writes to a friend on a printed card that was presumably readily available in the shops. He is writing from Helgoland (or, as it is known in English, Heligoland), that chip of sandstone thirty miles off the north German coast. The card shows a drawing of the island and below it a poem that describes the colours of the island’s flag, relating them to features of its landscape, each line in the appropriate colour.

In translation (and losing its rhymes) it reads:

The land is green,

The cliff is red,

The sand is white:

Those are the colours of Helgoland.

The land is green,

The cliff is red,

The sand is white:

Those are the colours of Helgoland.

The poem is in German, as is Sacher-Masoch’s letter. Helgoland is now a German-speaking island, part of the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. So German is it, that it was on Helgoland that the poet Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben wrote the song “Deutschland Über Alles”. However, Helgoland’s status is more complicated than it seems. Von Fallersleben was on Helgoland when he wrote the song in 1841 because he was in political exile from Prussia, having involved himself in liberal and nationalist agitation in the turbulent, divided Germany of the time. He had come here precisely because it did not belong to Prussia or to any of the other German states of the time: it belonged to the United Kingdom.

For much of its history Helgoland was left largely alone; notionally it was part of the duchy of Schleswig-Holstein which brought it eventually under Danish rule, but it was largely ignored. In 1807, however, it found itself in the way of global politics and was seized by the United Kingdom as a base that would enable it to maintain its blockade of Napoleonic Europe all the year round. Like Gibraltar one hundred years before, it remained a British possession after the immediate circumstances of its acquisition had passed and in 1814 the Treaty of Kiel formally ceded it to Britain.

The British royal family, of course, had strong links to Germany at this time which may well have made possession of Helgoland seem natural. (When I began researching this issue I was surprised to learn that the island was acquired so late and by force: I had assumed that it must have been part of the Kingdom of Hanover, which was linked to the British Crown from 1713.) This did not mean, however, that the latest colonial masters put any more resource into the island than Denmark had; it remained a footnote, without a proper harbour and with only a tiny garrison. The strongest link to Britain was the Union Jack now inset at one corner of the island’s red, white and green tricolour flag. By contrast, in Germany it was a subject of some interest: an enchanted island whose towering red sandstone cliffs contrasted with the low-lying, muddy Friesian coast to the south. Visitors included the future Kaiser Wilhelm II, who fell under its spell in the 1870s; other German-speaking intellectuals to visit included the composers Brückner and Mahler, and the writers Kafka, Kleist and – as we see – Sacher-Masoch. And as the nineteenth-century progressed, and Germany moved toward unification, pressure grew to bring Helgoland “back” within the German ambit, Prussia’s war with Denmark in the 1860s having brought Schleswig-Holstein (and thus the “original” title to ownership of the island) under Prussian rule, although the island itself had never been part of a German state and the islanders themselves spoke Frisian, the Germanic dialect close to English that is spoken along the coast and islands of northern Germany and the Netherlands.

For much of the nineteenth-century matters remained in this state: Britain, the owner of many far-flung island colonies, largely forgetful in administrative terms of this little close-up corner of the empire; Germany, increasingly assertive of its claims to represent all German-speakers. Queen Victoria, on the British throne, opposed any proposal to hand over British subjects to another power and may well have felt a kinship with them, as someone who had strong personal links to Germany through her own family and her marriage. To the Colonial Office, Helgoland was a useless anomaly, its garrison likely only to be a burden in time of war. As so often, Helgoland’s fate was decided by geopolitical events way beyond its control: in this case the Scramble for Africa. Germany and the United Kingdom were both engaged in colonial activity in East Africa, in Tanganyika (German East Africa) and Kenya respectively. British ambitions for continental dominion (and the Cape-to-Cairo railway) depended on curtailing German expansion inland, and the island of Zanzibar, off the coast of Tanganyika, was seen as a key to the area. In the late 1880s the Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, hatched a scheme to exchange Helgoland for Zanzibar, at that time a German protectorate, thereby, as he saw it, parting with a useless possession that happened to be craved by a colonial rival to gain something of far greater value. Despite fierce opposition from Queen Victoria, the measure eventually passed in July 1890 and the island was handed over almost immediately, on August 10th.

Sacher-Masoch’s card thus dates from the final months of British rule over the island, a time at which German interest in the island was at its height and behind the scenes, in the corridors of power, the British government was trying to get rid of it on the most advantageous terms. Immediately after the 1890 handover, imperial Germany set about trying to prove Britain wrong about the island’s military use by fortifying it. A generation later, as Britain and Germany went to war, who knows what use a British fortified base not far off the German shore might have been – a red sandstone Gibraltar or Malta, a thorn in the side of the German war effort, or an indefensible outpost overrun as quickly as the Channel Islands were in 1940. There is a counter-factual novel to be written, perhaps, set in British Heligoland in the interwar years, an enclave of holiday-makers and duty-free shoppers through which slip spies of various nations. Perhaps the Helgolanders themselves would say nothing has changed: in this alternative history, just as in the real one, their fate is decided far away by forces beyond their control.

Images of Helgoland are by joergens_mi and Oxfordian Kissuth.

-

CHRIS HILTON

Dr Christopher Hilton is a Senior Archivist at the Wellcome Library.

No comments:

Post a Comment